POLY PAGES

|

This essay was originally published on Medium on June 11, 2019. Medium removed it in late 2021 or early 2022 for unspecified policy violations. Requests to Medium's Trust and Safety department for clarification and reconsideration have gone unanswered. Find the survivors stories on I Tripped on the (Polyamorous) Missing Stair - Franklin Veaux (itrippedonthepolystair.com)

Franklin Veaux co-authored More Than Two[2] (MT2), a book about polyamorous relationships that many people admire, and also wrote a memoir called The Game Changer[3](GC). He has long offered advice to the public about how to conduct ethical polyamorous relationships, has toured to promote his books, and often gives interviews. Several of his past partners have lately accused him of causing them harm and trauma, including three ex-live-in (nesting) partners: they have testified to their experiences orally and in writing. His ex-nesting-partner Eve Rickert, his co-author on MT2 (who is, for reasons I will detail below, often given less credit for her work than she deserves), was the first to tell her story publicly. Despite extolling Eve’s[4] virtues for years, after the breakup Franklin began to publicly and repeatedly describe her as his “abusive ex” without naming her, though her identity was clear to most people who knew Franklin or even knew about him.[5] Eve began to publish essays, at first anonymously, that described her experiences with Franklin. She also began talking about her relationship with Franklin to some of his other ex-partners, including “Amber”, the titular character of GC. A disturbing pattern emerged in these stories: the polyamory expert who talked the talk consistently failed to walk the walk. Eve was in contact with Louisa Leontiades, who has written a series of books[6] about her own polyamorous relationships and who considered herself a friend to both Eve and Franklin. Louisa was initially reluctant to believe Eve’s stories, since she was also invested in Franklin’s narratives, but she after talking to others and reading the extensive documentation Eve provided she was convinced [7]. When Eve formed a “pod” to start a transformative justice process, she asked Louisa interview some of the women and collect their stories. Louisa, whohad recently returned to school to earn a Master’s in journalism, began to collect and curate testimony from people who had experienced harm in their relationships with Franklin. Louisa’s goal was to find out if the complaints documented a consistent pattern, and to provide those who testified with a platform for their stories, since Franklin had long dominated the narrative space. Louisa plans to write her Master’s thesis on the topic. Louisa collected testimonies and documentation ranging from LiveJournal entries dated decades ago, to recent email correspondences, to current phone interviews. In this piece, I discuss some of the documents I’ve been given permission to read and write about, some of the posts that surround them, and material Franklin has co-written or written — in particular, MT2 and The Game Changer, since several of the women who have testified were depicted in these books. Much of the public discussion about the testimonies and documents Louisa has been assembling has focused on whether the women’s testimony is “believable” or not, and, if believable, whether Franklin’s actions constitute “abuse.” Many people in the polyamorous community have chosen sides. The usual arguments have surfaced: denial and minimizing on Franklin’s part, along with claims that a woman (Eve or Louisa) is leading a witch hunt; those who accept the ex-partner testimonies usually point to the number of women who have come forward, the consistency of their testimony and the risks they were willing to take to testify. But I’d like to enter the discussion from another direction, because we have access to other materials as revealing as the testimony. The stories these women tell about their relationships with Franklin can be evaluated in light of Franklin’s own words, in the books that he has written and his other writings, published mainly online. The patterns his ex-partners describe are visible in these works — both in the stories he told and the way he told them. This article explores these patterns and serves as a corrective to attempts to isolate the women who have testified to relationship harm or abuse, to psychologize them, or to mask denial with claims to “objective” scholarship that undermines their testimony. Literary approaches like mine are disciplined rather than “scientific,” and can illuminate patterns and throw light on covert or even unconscious strategies that other forms of inquiry often miss. They do not reveal the internal lives and truths of subjects, and they cannot verify the truth of particular claims, but they can tell us quite a lot about how writers describe and organize their worlds. In this inquiry, when I talk about “Franklin,” “Eve,” and “Amber,” I am usually talking about their characters in various texts: how they narrate themselves, each other, their relationships, and their environments. Sometimes I refer to the “real-life” Franklin, Eve, or Amber (e.g., when I say that Franklin posted on Quora, or Eve wrote a diary entry). But I am clear, throughout, that I have no access to the internal lives of any of these people, nor do I need it to show that Franklin’s own work mirrors the patterns in the narratives that some of his ex-partners (in this essay, Eve and Amber) have shared. There is much debate over the best way to approach personal narratives and how to frame them. A range of experts, working in different disciplines, have tried to answer the question, but it is far from settled. This is why, when choosing a method of analysis, we still have argue its worth. Recently, Elisabeth (Eli) Sheff,[8] a member of Franklin’s pod, published a blog post critiquing Louisa’s interviewing technique and analytic methods. Eli, a court-appointed special advocate and sociologist, described her post as a “sociological analysis,” which I found curious. Since sociology investigates structural questions about society, groups, social relationships, and power structures, and Eli’s article did not situate the testimonies in their social context, I think it is better described as an “off-the-cuff ethnography.” In qualitative social science, professional interview-based ethnography usually relies on transcripts of interviews that are read and re-read until scholars can identify the main topics/ideas embodied in each section (sometimes in each sentence). Once we identify the topics, we sort them into categories, and then summarize the categories. If we’re doing academic ethnography, we usually need enough transcripts to reach “saturation” (which means that new transcripts do not give us new categories), and we rely on more than one coder, so that our interpretations are less likely to be affected by our biases. More coders are better, especially if they code independently and then come together to compare their results. Differences are discussed and usually resolved through consensus, but Eli did her work alone, on a very thin sample. Though I have published ethnographic peer-reviewed papers, I don’t think it’s a good method to use in this case, which is why I have instead chosen to take a feminist (not “the” feminist) approach that centers the survivors and to apply literary critical methods in narratology to a close reading of Franklin’s GC and Eve’s and Franklin’s MT2: I think that Franklin’s own work encodes the patterns of harm that his ex-partners describe. In the interests of feminist scholarship, I acknowledge my own subjective position. I’ve known the virtual Franklin (Tacit on both LiveJournal and OKCupid) for a long time —about 15 years. We corresponded, occasionally intensely, in the LiveJournal/OK Cupid days, and for a short time I edited and commented on an early draft of what would become More than Two (none of this remains in the published version, so I claim no contribution). Back then, I found Franklin’s advice on relationship freedom and honesty compelling, at least theoretically, because I’d had a long string of overlapping relationships — some of which worked out well, and some of which didn’t. When they didn’t, the root cause was usually dishonesty in the form of cheating behavior (occasionally mine, but usually my partner’s). I had reached a point where I realized lies are unethical because they strip people of their agency by manipulating their ability to make decisions based on good data. I was attracted to his work because the polyamorous relationships that Franklin promoted were based on honesty rather than lies. But I didn’t agree with Franklin about everything. For example, he shared with me a discussion he’d had with a woman who defended monogamy, and while I didn’t share her view that monogamy was inherently “better,” I also didn’t think some of Franklin’s responses were either fair or reasonable, and I said so. I enjoyed my discussions with Franklin, and we had no conflicts during this time, or before or after. We flirted mildly, but we lived far apart, and neither of us expressed any interest in interacting beyond the virtual intellectual realm. Our work on his draft tapered off at around the time that Amber (his nesting girlfriend and the pivotal character of GC) decided to leave for graduate school. Franklin and I fell out of all but occasional touch but remained on friendly terms, and it was Franklin who introduced me to Eve and Louisa when I took a train to Munich on a whim a couple of years ago to meet him face-to-face for the first time, during the MT2 European book tour. We all spent a pleasant evening together after the reading, in company with another friend. When we parted, we fell back into occasional communication. I did stay in touch with Louisa, with whom I had several long academic and personal conversations about scholarship on sexual abuse, and whom I began to consider a friend. My contact with Eve was limited to Facebook posts, much like my continuing casual contact with Franklin. I first heard about Eve’s experience of relationship abuse from Louisa, and then I spoke directly to Eve about it via email and Skype. I was allowed to read Eve’s and Amber’s long correspondence early on, and I went over it thoroughly, many times. My reading revealed a pattern of relationship abuse that gradually surfaced over the course of the correspondence, though both women were hesitant to name it. In their correspondence, Amber and Eve continually expressed concern about Franklin’s welfare and prospects, and consistently gave him the benefit of the doubt, even when faced with strong evidence that he had harmed them.

The belief that Franklin was unintentionally causing them serious harm, and that, if only he realized it, he would change, was consistent with his ex-partners’ choice of a transformative justice approach, which invites those who do harm to participate in a process of constructive self-reform, without driving them from the community. Partners of abusive men are often reluctant to acknowledge either the extent of harm, or the likelihood of intent. Patriarchy encourages women to invest in the narrative of a good man who does bad things, and to see themselves as the lifeline and savior of men who would otherwise be out of control. The alternative is often being cast in the role of victim, with an attendant loss of agency. Either choice can threaten women’s agency:

The women who have come forward with testimony and who drafted the documents I draw on are asserting their right to occupy narrative space that Franklin has so far dominated. I approach their narratives from the perspective of a trauma studies scholar, since that is my field.[9] I’ve spent much of my professional career interviewing trauma survivors (Holocaust survivors, rape and incest survivors, and combat veterans) and reading and analyzing their stories, both oral and written. I specialize in qualitative research in survivor communities, including difficult-to-interview communities where the lines between perpetrators and victims are blurred (e.g., combat veterans). I sometimes coach students in qualitative methods and advise on qualitative study set-up.[10] I brought this experience (and these methodological biases) to bear on my analysis, with the goal of illuminating Eve’s and Amber’s private stories, and contrasting them with Franklin’s public narrative of his relationships to see where they parallel and where they diverge. In this essay, I focus on a long correspondence between Amber and Eve, on some of Eve’s own notes and journal entries, on Eve’s and Franklin’s MT2, and on Franklin’s book, GC. The abuse that Franklin’s ex-partners describe surfaces like invisible writing in these texts when the flame of testimony is held beneath their pages.Hierarchies are encoded in texts just like they are encoded into social relations. Readers are often not conscious that their interpretations are affected by the structure of a book, and writers aren’t always conscious of the structures they’ve chosen, but literary critics are trained to notice and analyze the effect of structure on readers. We’re like geologists: we can read the history by looking at the layers under the surface. The structure of MT2, with its inset personal stories that mainly describe flawed female subjects, and its pattern of critiquing female behavior in the text while not acknowledging female authority, produces a landscape in which Franklin’s male voice dominates and echoes, giving the reader the impression Franklin is the narrator-expert. Franklin’s self-absorption and sexism is encoded in all his texts, like DNA. If Eli had coded GC alongside the three transcripts she wrote about [11], the structural aspects of Franklin’s “game” might have been clearer to her, and the irony of the book’s title would have emerged: there is nothing “game changing” about any of the women in Franklin’s universe. Metaphors matter, and designating certain woman as “game changers” (while other women are what? non-player characters?) is troubling, prima facie. Games are what Pick-Up Artists (PUA) play; games have score-cards: you win or you lose. Designating some women as “game changers” and others as… not… creates a hierarchy of importance, just as in the primary and secondary relationships that Franklin decries. If a woman is the game changer, this also relieves Franklin of responsibility for change. Franklin’s relationship universe in GC is like a pinball machine where he’s the ball: when some appealing new woman pops up, she can send him spinning off in a new, “game changing” direction… but it’s just Franklin’s trajectory and not the game that changes. Eve and Amber both make clear that Franklin’s nesting partners can count on being replaced, and then rewritten:

When he describes his two idealized “game changers,” Franklin is unstinting in his praise. He describes both partners as inspiring muses and helpmeets who support him, both personally and in his work. The benefits of these relationships were clear for Franklin, but I was struck by the contrast between his passionate declarations of gratitude and the lived experiences of the women he depicted:

Becoming a hero in one of Franklin’s stories might be flattering, but it came with a cost: one was no longer the main character of one’s own story.

Instead of offering a bold new take on relationships, the kind of polyamory Franklin promoted turned out to be an old form of oppression in a new dress. Amber took care to describe the structural nature of the problem: patriarchy’s habit of “using up women.” In her narrative, Franklin’s journey towards becoming a polyamory guru was patriarchal business as usual.

There are other warning signs that Franklin’s professed commitment to egalitarian polyamorous relationships may serve as cover for other traditional patriarchal attitudes. For example, Franklin has lately been claiming to be the subject of attacks by PUA and incels, and has discussed this on his Facebook page. During that discussion, I saw parallels between his approach to “getting women” and PUA strategies. Picking up the most women is a game you can win, and so is accruing girlfriends. The repetition of the phrase “five girlfriends” — a theme in Franklin’s social media posts and other writing — evokes the image of a winning poker hand. This “whoever has the most girlfriends wins” refrain was echoed by several other men in the comments: Franklin must be doing something right (“better” than incels) because the score is Franklin, 5; Incel, 0. There is, however, some cause to think Franklin’s “score” was inflated:

I prefer to engage in a different form of score-keeping. For example, in MT2, Franklin and Eve are listed as equal co-authors, and both have said repeatedly and in public that they made equal contributions to the book. But structurally, Eve is clearly subordinated. MT2 contains two types of writing: the first is the main text that flows through the chapters (the instructional text), and the second is a series of personal stories contained in inset boxes, illustrating points in the main text. Franklin’s authority is located in the main text, which is rife with examples of him doling out sage advice to rapt audiences or otherwise dispensing Solomonic wisdom. Despite his own protestations in the book and elsewhere, he’s constantly portrayed as an expert and not a learner. His presentation as an expert is not interrupted until he shares a story about Ruby, but this story is immediately followed by a penetrating insight that appears to forever resolve all his problems with jealousy. Then MT2 goes right back to mentioning his expertise almost every time he is named, except in brief discussions of his lack of agency in his relationship with Celeste, his poor treatment of Bella (which is also shown as ultimately Celeste’s responsibility), and a few other minor incidents. On the rare occasions Franklin does tell a personal story, it almost never portrays him as vulnerable. In contrast, the personal stories told by Eve and other women in MT2 show that they have made mistakes, learned, and grown (or failed to grow) from their experiences. Franklin is almost never featured that way — he is positioned as the expert, and “his” stories usually detail other people’s failings or describe his accomplishments. In MT2, Eve is Exhibit A, over and over again, admitting flaws and facing problems, while Franklin remains largely outside this process, explaining and passing judgment. This power differential strips Eve of agency, while degrading her position as an authority on her own life — a central component of gaslighting. MT2 emphasizes Franklin’s expertise at Eve’s expense. Franklin’s name is mentioned 166 times in MT2 (over 60% of mentions): 141 times in the main text (85%) and 25 times (15%) under FRANKLIN’S STORY headers.[12] When his name appears in the text of the book, it’s accompanied by constant repetition of phrases like, “Franklin has received scores/hundreds/thousands of emails…” “Franklin calls this…” “Franklin’s most controversial blog post…” and other sorts of authoritative speech. Eve’s name, which rarely appears next to claims of authority, is mentioned 99 times (less than 40% of mentions): 73 times (74%) in the main text and 26 times (26%) in EVE’S STORY headers. When Eve’s name is mentioned in the text, she is mainly posited as an example. In MT2, Eve is frequently personalized and the object of scrutiny, while Franklin is promoted as an objective authority, a role model, and the conduit for knowledge. Eve appears in the main text far more often as a subject to be discussed; Franklin is almost always represented as the qualified expert. Even though both Eve and Franklin have said that she wrote as much or more of the main text as Franklin did (referring to herself in the third person) the structure of MT2 creates the impression in the reader that Franklin is doing the talking and not Eve — which may account for the audience’s perception that she is a lesser co-author. The more I looked at the male characters in MT2, the more it became evident that men were weirdly absent from the book, as was any discussion of gender roles (and especially gender imbalances) in relationships. So many of the negative stories in MT2 are about women damaging other women, or damaging men because of their jealousies and insecurities. In general, women get the blame for problems, and men tend to be described as proximate causes. In one of the few stories in which a guy behaves badly (Meadow & her husband), MT2’s intent was not to point out that Meadow’s husband was treating her badly, but to emphasize Franklin’s victory in an unspoken competition: Meadow’s husband was jealous because Meadow liked being with Franklin so much. This competition is a defining aspect of Franklin’s textual worlds: he writes himself as the alpha male center (in the sheep’s clothing of a sensitive feminist guy), surrounded by orbiting women who might be incidentally attached to other guys, but who are only important because of their attachment to him.

In GC, attachment to Franklin is the only authentic attachment: women’s relationships and interactions are important only as far as they relate to him. The Franklin who is depicted in the testimonies of his ex-partners looks for and finds women who will center him: he grooms them and then exploits them until they can’t take it anymore. He demonizes them or idealizes them. And then he still exploits them, after they’ve gone, by appropriating their stories and using them as bait to catch (and object lessons to discipline) other women he will eventually put through the same process. His work can’t even pass the Bechdel test: women don’t exist for him unless he intersects with them sexually, and he cannot seem to imagine women’s relationships with each other except as competitions for his attention.

In GC, male characters are described as mentally healthy, but most female characters (except the game-changer) are not. Men are benign, autonomous, well-adjusted people — their involvement with women is a part, but not the central pillar, of their lives. The men in GC are not insecure, but they can be motivated to do unhealthy things to please the insecure women around them. Franklin’s men have little interior life. He does not psychologize men’s relationship choices like he does those of women. His men are basically happy; when they are unhappy, their distress is attributable to a woman’s behavior. His male characters never reflect on their privilege, and they take for granted a level of freedom and autonomy that women can rarely match:

His ex-partners, however, see this freedom and autonomy as an illusion upheld by their unacknowledged and unappreciated labor, and see Franklin as supported by a community of women:

Both Amber and Eve emphasize Franklin’s financial dependence upon them, and the heavy price they paid to sustain his desired lifestyle:

Franklin depicts himself at the center of a universe that revolves around him, in which his relationships with women are primarily premised on their fuckability-to-hassle ratio. Despite his preoccupation with the psychology of his women characters (“what do women want?”), Franklin provides only the shallowest explanations for their thoughts and actions. As Eve noted in a later reflection, Franklin “…treats the things that upset me as these mysterious, unpredictable things (‘bitches be crazy’) instead of things he can understand and incorporate into his worldview and future behaviour.” [Eve, journal entry, March 11,2018]. In MT2, women’s problems are also reduced to a set of unreasonable insecurities and fears, which they could overcome if they “chose” to do so:

Failure to make the correct “choice” turns women into abusers. In GC, for example, Celeste’s jealousy causes her to disregard the humanity of Franklin’s other partners, and this leads her to victimize Elaine. Throughout GC, pain is the emotion that characterizes women’s lives, whether they suffer it or inflict it.

His partners also see pain as a constant in Franklin’s relationships, but they point to a different source. For them, women’s pain is not a mysterious product of their own unreasonable decision to be jealous, but a product of Franklin’s inability (or refusal) to understand the harm he is doing the women in his life.

The conflict in GC is a product of Franklin’s attempts to be free (polyamorous), and Celeste-the-character’s attempts to rein him in. Celeste’s discomfort with polyamory is posed as the problem; her character has a zero-sum approach to relationships, and she is consumed with unwarranted jealousy. To live a fully polyamorous life, Franklin must extricate himself from the trap his marriage has created for him. The heavily idealized Amber is his beacon of freedom. The narrative suggests that, once Franklin leaves Celeste for Amber (symbolically leaving the slavery of monogamy for the freedom of polyamory), the future promises smooth sailing on the sea of polyamorous self-discovery. But this did not turn out to be the case for Franklin-the-real, since his personal history continued with a series of new “game changers,” and a string of ex-nesting partners and lovers who no longer want contact with him. The reality is strongly at odds with his public persona. Doling out relationship advice on Quora, Franklin wrote:

But Eve’s calculations, based on Franklin’s own descriptions of his relationship history to her and her conversations with some of his exes, throw Franklin’s claims into question: Total is 18, of which he’s friendly with 3 and has no contact with 13. Has contact with 0/4 nesting partners[13]. For last 13 relationships it’s always a story where he was victimized. (Eve’s consolidated notes from Spring 2018) Franklin’s bar here is low (“at least one ex”) and easy to meet if you move through many relationships, but a 1:6 “friendliness” ratio is disturbing for a man who has become the face of the “ethical” polyamory movement, and could be explained by his tendency to play partners off each other in order to maintain control over them

In GC, women’s stories are histories of their jealousies, and interactions between women become tense or hostile because they are too possessive. Jealousy belongs to women, and men are free from responsibility for creating or cultivating it. "Celeste didn’t like Blossom one bit, and the feeling was mutual. After that painfully awkward first meeting, Celeste took me aside and said, “Her? Really?” (GC, https://bit.ly/2I4OKj5) But the view from the other side is quite different:

When his partners and ex-partners began talking to each other instead of allowing Franklin to mediate their communications, Franklin’s game became visible: T2 repeatedly underlines the importance of taking personal responsibility for feelings of jealousy, but it never tackles the question of whether or not men can deliberately evoke jealousy in their partners, and then use it as a tool for manipulation or coercion. GCalso sidesteps this question with its portrayal of jealousy as an inherent, almost entirely feminine failure of character that women must learn to overcome. But in the relationship narratives, both Eve and Amber note Franklin’s tendency to use jealousy to control the relationship. Eve speaks explicitly about the disjunct between the narrative she and Franklin created about jealousy in MT2 and the role jealousy played in their relationship life:

Just as Franklin considers women responsible for their own jealousy, he assumes little responsibility for other relationship problems in GC. For him, relationship problems are indicators that his partners need to fix themselves. His behaviour is rarely at issue, except insofar as he allows himself to be caged in an unsuitable relationship, but he depicts his partners as insecure, anxious, mentally ill, controlling, and/or abusive. Franklin consistently collapses the wide range of women’s complex emotions into a small subset that he repeatedly details: jealousy, insecurity, anger. This simplification allows Franklin-the-author to center Franklin-the-character, who is repeatedly victimized by women who behave badly:

Evidence that Franklin is capable of compassion is lacking in both MT2 and GC, where the reader is more likely to be treated to lectures on personal responsibility and catalogs of the flaws in women’s personalities. Franklin’s flaws, insofar as he admits them, are mainly portrayed as the products of Celeste’s bad behavior and his reactions to their toxic relationship. This deflection of blame is characteristic of gaslighting, where some abusers justify their behavior by claiming the victim has inherent flaws that “make” them behave in a particular way. Eve’s narrative suggests that Franklin’s consistent refusal of responsibility for his partners’ pain throughout both GC and MT2 can be interpreted as a passive-aggressive strategy of coercive control:

In GC, this passivity comes out in the navel-gazing and deflection his character mistakes for self-reflection, and in his sophomoric philosophizing. Though Franklin self-presents as an objective and analytical narrator, he can only interpret others’ behavior based on his interior model of “how people work.” The model is fitted to the data, rather than derived from it, which gives Franklin’s character tunnel vision. In Amber’s narrative, Franklin holds tight to his model even after she shows, time and again, that it is inaccurate and damaging to her.

Since the younger Franklin of GC is perpetually bewildered by the women in his life, who make no sense to him, we can read MT2 as the manual he is determined to write so he can stay out of trouble. Throughout bothGC and MT2, his analysis of human behavior is mechanistic (press this button, then that happens) rather than complex, again evoking the mechanistic games of the PUA. Mechanistic approaches appeal to those who feel they cannot control their world; it is comforting to believe that given the right lever and a good place to stand, one can move the world, others, or oneself. A self-proclaimed expert who promotes the idea that his control mechanism will solve common problems can attract insecure followers who are also looking to exert control. If belief in the mechanism is strong enough, and the expert is charismatic enough, people can be convinced of just about anything. His ex-partners depict Franklin as an expert manipulator of women’s weaknesses and a recruiter to the Cult of Franklin.

When an inadequate mechanism fails a believer, the expert is unlikely to re-evaluate his model, especially if it is central to his self-concept; he is much more likely to cast blame on the now-questioning believer and double-down on the claim that the mechanism works, if only the believer would just use it correctly. In abusive relationships, this is a form of gaslighting:

One of the benefits of being considered an expert and providing a group of followers with an appealing control mechanism is that you have followers whom you can dispense to attack challengers. Franklin’s perspective often informs the work of others, whether or not they are aware they are being led in this fashion. This has been evident in the reactions of segments of the polyamorous community to his ex-partners’ efforts to bring their narratives to the fore. To illustrate this problem, I return here to Eli’s “objective” article about Franklin’s partners’ testimony. Given my training, I am hyper-aware of framing (the contexts in which stories are told). I am not sure Eli thought much about what it meant to frame her discussion of the three survivor testimonies between harsh critiques of Louisa’s approach and methods, but this tactic centered Louisa as Eli’s target, and sidelined Elaine’s, Celeste’s and Amber’s testimony, which Eli deployed as evidence Louisa’s work was inadequate and ethically compromised — an argument that I do not think holds water, and that Louisa has already addressed in detail.[14] I question the ethics of first dismissing the chosen advocate of women who have testified to harm, and then appropriating those testimonies without their consent. Displacing Louisa, who collected and was invited to discuss the testimonies, is a power move. But why choose this course? The structure of Eli’s essay trivializes and minimizes the harms that Franklin’s ex-partners describe. Though she, for example, acknowledges “strong and consistent themes that warrant serious attention,” she diminishes the impact of her charge by writing, “some of Franklin’s ex’s accuse him…” where she might more accurately have said, “three of Franklin’s ex-partners, including two long-term nesting partners, describe, in remarkably similar terms, the ways Franklin emotionally harmed them.” Her summary of Franklin’s “source of power” is equally troubling, where she uses psychological jargon to obfuscate rather than illuminate:

Instead of saying, “Franklin appears to use lies and emotional manipulation to persuade the women who love him to bend to his will,” Eli creates a narrative in which Franklin is Svengali and his ex-partners are weak-minded, emotionally needy puppets. She does not conclude they were led to make bad decisions because they were presented with manipulated evidence or coerced — she makes them victims of their own love and their dependent personalities. Eli doubles down on this antifeminist argument by claiming that Louisa has twisted and influenced the testimony of his ex-partners by asking “leading questions,” ignoring evidence that Franklin’s ex-partners had definite opinions, submitted their own documents, read and commented on the testimonies Louisa transcribed, supplemented them, and suggested amendments. Nowhere does she address the struggle for agency and recognition as equal persons that the testimony emphasizes. Demonizing Louisa and turning the women who testified into pawns distracts the reader from the testimonies and the women who wrote them, casts doubt on their authority and validity, and robs them of their main purpose, which is to point outthat Franklin, self-proclaimed nice guy and polyamory guru, is a hypocrite who harms women, benefits from their pain, and colonizes their histories. Eli’s narrative of distraction can only work to Franklin’s benefit, which is why he frequently deploys it himself: for example, in a series of (since deleted) public posts[15] in which he claimed that his “abusive ex” (Eve) was the mastermind behind all the complaints that his other ex-partners made, and that she was turning the rest of them against him. These are really not the kind of “explanations” we want within spitting distance of survivor testimonies. By reducing women’s agency to a kind of Pavlovian response to giving and withholding affection and an essential weakness of character, Eli sidesteps the structural aspects of Franklin’s modus operandi. For example, she fails to mention the pattern of triangulation that Franklin’s ex-partners consistently describe: the shiny new girlfriend is fed stories about a damaged and needy current nesting partner and actively encouraged to take Franklin’s side. When the shine wears off the new partner, Franklin finds another mark and again describes his current nesting partner as damaged and problematic, in a cycle that is hard to distinguish from the “serial monogamy” patterns Franklin has spent years condemning. (Again, this is “the game.”) On the sidelines of the game, in Franklin’s cheering section, is a polyamorous community (also operating within a patriarchal structure) that accepts his descriptions of his partners, ex-partners, and relationships as accurate, and even uses them as models for their own polyamorous relationships. The women who stand up to Franklin are pitted against this community — all the people who have invested in him and the lifestyle and methods he promotes. Eli never examines the context in which Franklin’s ex-partners have gained what small power they now have: these women have worked together to confirm the reality of each other’s experiences. But they can sustain this effort only if they have the support of other community members who serve as a bulwark against attacks and attempts by Franklin and his supporters to delegitimize them and shut them down. With her article, Eli steps in as a Franklin supporter who accepts and asserts, without offering supporting evidence or argument, that Eve is the “real” abuser. She issues a brisk recommendation that Eve be banished from her own support pod to protect Franklin from revictimization.

Though Eli emphasized her “objectivity” in her post, and in her responses to critiques (e.g., her claim, in Louisa’s Facebook comments feed[16], that her “analysis is much more balanced and factual than [Louisa’s] interpretations”[17]), her recommendation is starkly partisan, given the number of testimonies collected to document Franklin’s behavior and absent documentation of Eve’s abuse beyond Franklin’s assertion. She also ignores the testimony that throws into question the stories Franklin has been telling about women:

Eli is not the only member of Franklin’s pod to go on the attack. The winner in the “Embarrassing Male Allies” categories has to be Stan, a self-proclaimed “independent” supporter (“not just a hardware engineering badass — also, a feminist”), whose toxic male bluster includes knowing “a fuckton about governance” and “sexual harassment.” His new-sheriff swagger is marked by hyperbole and contempt for the project Franklin’s pod was allegedly formed to advance:

Like Eli, he claims to be the voice of objectivity and truth: “I also deal in fact. Not allegation. Not rumor. Not gossip. Not social media rumblings.” He’s, by God, gonna clean up this town: "I’ve read all the published information, including rumor and innuendo, and have discussed this with the other members of the pod. There’s a lot of smoke, and a lot of facts which create causal linkages that strongly imply there’s more going on here than meets the eye, that there may be motive at work which colors strongly the process." Stan grudgingly acknowledges the “non-zero probability” that the stories about Franklin are true, and that Franklin may have been hiding behind a do-right public persona, but his main concern (and apparent presumption) is that the women who have described harm are conducting a smear campaign (echoing the narrative in Franklin’s deleted posts). To circumvent this, he claims that “we — the pod” will establish “a system to independently solicit and investigate claims made against Franklin… conducted in a way that ensures the anonymity of the claimant to Franklin so that there is no room for potential reprisal, yet also provides communication pathways between the pod (and other investigators as needed) and the claimant.” This process will (somehow) “hold those with claims against him accountable to not make false claims.” Stan ends his Quora post with a rally-the-troops call for good men everywhere to stand up to bad women: "Why? Because Franklin may in point of fact be exactly who he was previously believed to be. And it’s critical, in seeking justice for offenses, to remember that the goal of justice is to protect the innocent — whether that is the person making a claim, or the accused." And, as if his prose wasn’t quite a deep enough shade of purple, Stan finishes with this flourish: “Astute observers of human nature will note that it’s one tiny step from “J’accuse!” to Robespierre, and the Reign of Terror…. Not on my watch.” Details on how, exactly, Franklin’s pod will protect Liberty, Equality, and… Fraternity are apparently forthcoming. With friends like Stan, I doubt Franklin needs enemies. But the difference between Eli’s more understated position and Stan’s is only a matter of degree. First, both doubt the authenticity of the collected testimonies, on no basis other than that… they doubt them. Both rally around Franklin to protect him from women with ill intent. Both spend time working to discredit and undermine the transformative justice structure that justifies the existence of their “pod.” Instead, they use the formal structure of the pod to maintain existing power structures, while also positioning Franklin, who continues to have a platform in polyamorous communities, as a victim. Even if Eve was an abuser (as she claims Franklin is), in transformative justice, both perpetrator(s) and victim(s) of harm are essential to the community-based process of changing abusive behavior and making restitution for it within a supportive yet firm community dedicated to reconciliation and justice. I have reservations about transformative justice, because members of structurally oppressed groups (e.g., women) cannot force structurally powerful abusers (e.g., men) to change. Few abusers are willing to humble themselves and put in the effort to change, and to — let’s be clear about this — give up the benefits of being an abuser, though they are often quite willing to exploit the transformative justice process as long as they feel they can benefit by doing so. Though, theoretically, transformative justice can be achieved by a community even if the perpetrator refuses to participate, few communities aren’t, at root, committed to the structural inequalities that sustain abuse, so perps are often let off the hook. Like Eli, I don’t take a transformative justice perspective. But unlike Eli, I know better than to disrupt the process by making recommendations that undermine a project that survivors support, which is why you’ll find no recommendations here. Instead, I’ve given you a portrait of a writer who made himself the main character in the stories of the women whose voices he appropriated. He stripped his female characters of agency and turned them into puppets for an audience already primed to see women as either idealized “game changers” or damaged goods. In this process, his ex-partners suggest, the models Franklin created were more real to him than the women themselves. The reality he saw was so different from that of his partners that they might as well have been in different universes. The attachment Franklin has to his models is so deep, his ex-partners explain, that when they violate his expectations, punishment and gaslighting swiftly follow. When partners step outside their assigned role, domestic abusers often see this as a threat to their control and react violently. Emotional abusers are more likely to respond with words or body language that signals anger, coldness, or withdrawal. In either case, abusers are likely to blame the victim for “forcing” them to abuse. Abuse often abates or ceases when the victim retreats back into their idealized role. In this scenario, the abuser generally feels like the victim.

Many men have difficulty accepting women’s anger, no matter how it is expressed. Anger is one of the few emotions allowed to men by patriarchal culture, perhaps because it is essential to securing their power. Maybe this is why women’s anger often triggers an abuser, no matter how mildly it is expressed. Franklin has publicly and repeatedly referred to Eve’s “anger problem,” but she describes the problem very differently:

Anger is a form of agency, an assertion of subjectivity and a claim to rights. In an abusive relationship, the anger of the victim can threaten the abuser’s carefully curated construct and challenge his image of himself as a good man. Even simple assertiveness, without anger, can trigger this response, which is why, given Franklin’s investment in the malleable nature of the women he represents in his work, and his consistent misrepresentation of their reality, I doubt his characterization of Eve as an abuser. Like any memoirist, Franklin tells other people’s stories along with his own, formulating them to suit his particular agendas, which may include promoting a lifestyle he believes in, showing himself to best advantage, enhancing his reputation, making money, and finding new relationship partners. None of these pursuits is inherently unethical. What determines the ethical nature of the endeavor is the honesty of his representations of self, the accuracy of his representations of others, the level of consent he receives from his subjects, and what he does with the rewards he reaps. In my reading of GC and MT2, Franklin’s own storytelling patterns are compatible with the narratives of relationship harm and abuse written by his ex-partners. © Kali Tal, PhD, 2022 [Note: Eve granted me permission to read, analyze, and excerpt her correspondence with Amber. Amber granted Eve written permission to share her correspondence with me, and allowed me to quote from it. Both Eve and Louisa commented on the manuscript. At Amber’s request, we did not ask her to review this manuscript before publication.]

[1] Quotes from Eve’s and Amber’s email exchange and Eve’s notes are reproduced exactly and were not edited for spelling or grammar. I do substitute women’s pseudonyms and delete names from the text where appropriate, and in one or two cases I inserted a word to clarify meaning. These are set off with brackets to clearly indicate the changes in the text. [2] Franklin Veaux & Eve Rickert, More Than Two: A Practical Guide to Ethical Polyamory (Portland, OR: Thorntree Press) 2014. [3] Franklin Veaux, The Game Changer: A Memoir of Disruptive Love(Portland, OR: Thorntree Press) 2015. [4] I use first names, throughout, for women who testify and for those who comment on their testimony. Most of the women who testify use first-name pseudonyms, and Franklin and Eve refer to themselves by their first names in their books. I made the decision to use first names so I could remain consistent and, rhetorically, preserve equity between the women who testified and the critics who write about them. [5] https://polyamory-metoo.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Original-Quora-answer-02_11_19.png; https://polyamory-metoo.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Screenshot_20190211-FV-Quora-re-public-statement.jpg [6] The Husband Swap series: http://louisaleontiades.com/the-husband-swap-series [7] http://louisaleontiades.com/metoo-motivations [8] Dr. Elisabeth Sheff (https://elisabethsheff.com; https://scholar.google.ch/citations?hl=en&user=iDc-3tUAAAAJ), herein referred to as Eli for reasons specified in footnote #2. [9] https://kalital.com/trauma-studies [10] For publications and credentials, see https://scholar.google.ch/citations?user=8Lpw8x4AAAAJ&hl=en. [11] Eli did wax rhapsodic about GC in in June 2016 (https://elisabethsheff.com/2015/06/12/review-of-the-game-changer-by-franklin-veaux/) in a short (284 words) review full of glowing adjectives: fresh; authentic; poignant; entertaining; educational, candid, thought-provoking, deep, witty, frank. Somehow, she missed the fact that in his “searing self-critique” Franklin had chiefly blamed women for his unhappiness and their own. [12] I checked this by using Microsoft Word’s “find” function in the Search pane, based on a pdf version of the book that I converted to Word in Calibre. Since I didn’t entirely trust the accuracy of the search, I counted two chapters by hand, with similar results. Given my rather crude methods, I won’t swear you will get exactly the same results if you do your own search, but I am sure you will find the same patterns. [13] Eve’s calculation includes Ruby as a nesting partner; Louisa’s research suggests the count might more accurately be 0/3. [14] http://louisaleontiades.com/response-to-dr-elisabeth-sheffs-critique-of-voices-from-the-game-changer/ [15] https://polyamory-metoo.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Original-Quora-answer-02_11_19.png; https://polyamory-metoo.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Screenshot_20190211-FV-Quora-re-public-statement.jpg [16] https://www.facebook.com/LouisaLeontiadesWriter/posts/2260757244141699 [17] https://bit.ly/2K4HZjB [18] All quotes from Stan are extracted from this Quora post.

1 Comment

Freephone 24-hr National Abuse Helplines USA: 800-832-1901 (The Network/La Red) UK: 0808 2000 247 (Refuge) The below resources have been compiled by Claire Louise Travers and The Network/La Red for Poly Pages to accompany a Poly Pages event. Abuse is a pattern of behaviour with the design, intent or consequence of making someone unable to leave a relationship/situation Partner Abuse is a systemic pattern of behaviours where one person non-consensually uses power to try to control the thoughts, beliefs, actions, body and/or spirit of a partner. This can happen in lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, polyamorous, SM/kink and straight communities. Partner may refer to a range of intimate relationships including but not limited to play partners, date, primary, secondary, spouse, sexual partners, boyfriend/girlfriend, boo, hookup, life partner or lover. Partner Abuse is also called domestic violence, battering, inimate partner abuse, and/or dating violence.

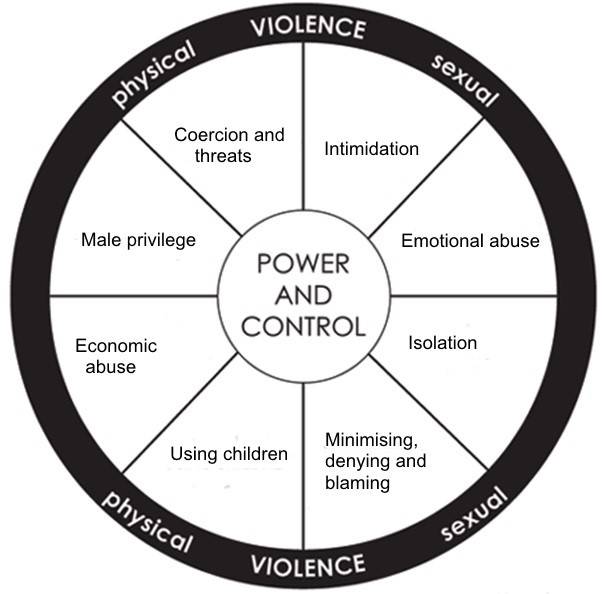

The theoretical and cultural understandings of how abuse operates, presents and the impacts it has on individuals and communities, still not inclusive of the experiences of non-monogamous relationships. Services providers, literature and general information available about abuse assume a monogamous relationship, and as such individuals seeking support and information are just as likely to be alienates and ostracised as they are to be helped - polyamory or non-monogamy is likely to be understood as a symptom of the abuse or a tool of the abuser. While many of the red flags and tactics of abuse may be similar to dyadic or monogamous relationships, without explicitly expanding our definitions and concepts to include non-monogamy, we allow tactics in non-monogamous relationships to become invisible and un-named. When something is unnamed, unlabelled or without reference, it becomes much harder to talk about it and call out abusive behaviour. And this is exactly what has happened. From the well-documented decades of abuse by Franklin Veaux, to the recent legal case against Eliot Winter for human trafficking and sexual assault, polyamory has become a hunting ground, refuge or fertile soil for men who wish to harm, control and exploit women. As such, there is a need for tools to taxonomically catalogue, the various strategies used for abuse in polyamory and account for how they present in non-monogamous relationships. The Duluth Wheel of Power and Control is one such tool: a visual resource to aid us in a comprehensive understanding of the tactics used by abusers, and how these tactics interact to maintain control and power in a relationship. History: In 1984, staff at the Domestic Abuse Intervention Project (DAIP) in Duluth, Minnesota began developing a curricula for groups on "men who batter and victims of domestic violence". They wanted a way to describe "battering" for victims, offenders, practitioners in the criminal justice system and the general public. Over several months, and through many focus groups with women who had been "battered" they documented the most common abusive behaviours or tactics that were used against these women. The tactics chosen for the wheel were those that were most universally experienced by victims of domestic assault and violence. The wheel is a product of it's time and so uses highly gendered languages, as-well as being very mono- and hetero- normative. This is a deliberate and concious choice by the DAIP who claims that the week "does not attempt to give a broad understanding of all violence in the home or community but instead offers a more precise explanation of the tactics men use to batter women."

What does it look like?

CLAIRE LOUISE TRAVERSThis is (c) Claire Louise Travers: an academic author, researcher and polyamorous community organiser. You can tip here on PayPal: @claireltravers |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed